Malcom X

By Marcus McGee August 18, 2021

Despite self-delusions, we are all products of the set of experiences that begin from the moment of our conception. As humans, we are less instinctual and more affected by genetics, environment, and in a few cases, the unique ability to rise above it all. The outcome is the story of a life.

Malcom Little was born in Omaha, Nebraska, to parents Earl Little and Grenada-born Louise Little (nee Norton) on May 19, 1925, 60 years after the end of slavery in America. The Great Northward Migration, or the Black Migration, in the United States had begun in 1916 and extended to 1970, involving the resettlement of six million Blacks from the segregated Jim Crow South to America’s cities in the North and West. In 1910, Omaha had the third largest Black population among western cities.

Omaha, with jobs in the meat-packing industry and other related jobs, was a better place, though Blacks were concentrated/segregated in North Omaha and resentment and violence against Blacks there and in other industrial cities was ever-present. The summer of 1919 was called “Red Summer,” a time in which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots (translation: white mobs converging on Black neighborhoods before looting, burning and murdering men, women and children) took place in dozens of cities across America, shortly preceding the Tulsa race massacre in early 1921.

Malcom was the fourth of seven children born to Earl, who was an “outspoken troublemaker” to the Omaha white establishment and an advocate of Marcus Garvey, Black self-reliance and Black pride. Under threat from the local Ku Klux Klan, he moved the family to Milwaukee a year after Malcom was born and soon thereafter to Lansing, Michigan.

When Malcom was six, his father was murdered by whites. The city officially ruled his death “a streetcar accident,” while the insurance examiner called it a “suicide,” and yet considering the death of Sandra Bland in 2015 (she was found hanged three days after being arrested in a routine traffic stop, officially ruled a suicide), in 1931 the cause of death for a Black man was whatever was deemed expedient by authorities. When he was 13, Malcom’s mother had a nervous breakdown and was committed to Kalamazoo State Hospital. Malcom and siblings were separated and sent to foster homes.

Obviously intelligent, he became disillusioned with the goals of education when, after revealing his desire to go to law school, a white teacher insisted that lawyering was “no realistic goal for a nigger.” After dropping out of high school, he moved to Roxbury in Boston, where he worked odd jobs while living with his sister. He moved for a short time to New York City’s Harlem neighborhood before returning to Boston as a 20-year-old with no high school diploma and no real job skills.

Facing a dead-end future, he learned the ephemeral nature of a criminal life when he was arrested for burglary a year later and sent to Charlestown State Prison ten years. While locked up, Malcom met fellow convict John Bembry, a respectable, self-educated man who re-inspired Malcom to pursue reading, knowledge and learning. Shortly thereafter, his siblings introduced him to the teachings of the Nation of Islam, a Black nationalist organization that taught Black superiority, Black separatism and beliefs that white people were inherently violent and wicked. Malcom’s life experiences had conditioned him to resent whites, so it was not difficult for him to embrace the frustration and hate felt by many in the persecuted and oppressed Black community, beginning with the prison population. He became a believer in God, adhering to a clean lifestyle while refraining from consuming alcohol and eating pork.

And so Malcom , who had entered prison as a inquisitive though disillusioned and desperate youth emerged from incarceration as a strong, self-educated and inspired man. He had found strength in his belief that the Nation of Islam and its teachings held the promise for a cure to Black poverty of position, education, dignity and spirit. At 23, he had begun a correspondence with NOI leader Elijah Muhammad and joined the organization, transforming from Malcom Little to Malcom X, substituting “X” for the original name that “some blue-eyed devil had imposed upon his paternal forbearers.”

Paroled at 27, Malcom visited Elijah Muhammad in Chicago and began his ministry with the Nation of Islam, primarily in recruitment for membership. He was assigned to Temple Number One in Detroit, and he established many more over time. He came to America’s consciousness five years later when he intervened on behalf of Hinton Johnson, an NOI member who had been savagely beaten by two New York City police officers. In a show of support, four thousand NOI protesters gathered outside the police station, and after negotiations with police, Malcom dispersed that huge crowd with a mere hand signal. That subtle display of that power caused the wary NYPD to place him under constant surveillance from that point on.

A successful recruiter for the Nation of Islam, Malcom was credited for the group’s dramatic expansion in membership, which by modest accounts increased from 500 members to 25,000 members, and by a more generous estimate from 1,200 to 50,000 or 75,000 members. Iconic young boxer Cassius Clay, inspired by Malcom, became Muhammad Ali, and Malcom mentored and guided protégé “Louis X,” who later became the leader of NOI as Louis Farrakhan. To his father’s honor, Malcom had found his calling as a powerful recruiter for a Black empowerment movement.

The “nurture” without told him to embrace his Blackness and the pride and objectives of his race and the Nation of Islam, while the “nature” within urged him to fight with everything he believed for his painfully-wrought values and beliefs, and to follow his own deeply-ingrained moral compass, inherited from his parents through both nature and nurture.

Malcom vs. the Civil Rights Movement

During the 1950s-1960s, the philosophy of the Nation of Islam came to confront the tenets of the civil rights movement and its leaders. As Malcom’s influence grew in the Black community, Black leaders and the NAACP grew alarmed with his teachings of Black separatism as they struggled to integrate America through civil disobedience and protests, where they were being violently beaten and arrested, and marshalling the support of many whites. They were at odds with the Nation of Islam for forbidding its members to vote as civil rights leaders and a movement marched and sacrificed their safety and very lives for a congressional voting rights act.

When asked to take a position, the NAACP and civil rights leaders stridently condemned the Nation of Islam’s teachings and Malcom X, who had become the face of the competing movement. Popular Black leaders called him and his group “irresponsible extremists whose views did not represent the common interests of Blacks in America.”

Malcom took up the challenge and engaged in the national debate, asserting that civil rights movement leaders were “stooges” of the white establishment, and he eagerly engaged in interviews during which he advanced his counter argument to the goals of civil rights leaders. He called Martin Luther King, Jr. a “chump” and said the 1963 “March on Washington” should have been called the “Farce on Washington” for a demonstration “run by whites in front of a statue of a president who has been dead for a hundred years and who didn’t like us when he was alive.”

Malcom believed the principles of “nonviolent resistance” were weak and unrealistic and argued that “violence” is the only language that violent people understand. He thought that Blacks should, first and foremost, defend and advance themselves. Some have mistaken his criticism of nonviolence to mean that he was an advocate of “violent resistance,” and overthrowing the government, which was not true. However, he encouraged his followers to assert their rights and freedom and to arm and defend themselves when necessary.

Over time, Malcom’s increasing popularity resulted in increasing friction, since while many saw him as the face of the Nation of Islam, its actual spiritual leader, Elijah Muhammed, subtly sought to assert the power of his position. Careful not to upstage his mentor, Malcom never took credit for even his own ideas, arguments and insights, instead beginning answers and statements with “The Honorable Elijah Muhammed, our leader, teaches us that…” Notwithstanding, a schism between the two was inevitable.

Enlightenment

As the movement grew, local police departments felt threatened by NOI members’ sense of defiance and their willingness to defend themselves, though no where was the perceived threat greater than it was in south central Los Angeles, where violent LAPD officers beat and murdered Blacks regularly. In April 1962, two officers, without cause, caught and beat a group of NOI members outside Temple 27, resulting in a large crowd of incensed members rushing out from the temple to confront the violence.

Rather than physically attacking the officers, the angry though restrained crowd disarmed them, yet the escalation had already begun. Within minutes, more than 70 agitated backup officers arrived. Without hesitation, they raided the mosque and randomly beat members inside. Drawing firearms in a place of worship, they shot seven members, including two in the back (the Korean War veteran was paralyzed for life; and the man raising his hands over his head to surrender died from the gunshot wounds).

Malcom was outraged and considered the violation of the mosque a sacrilege, vowing vengeance and retribution against the Los Angeles police. Thus assembling a group of street-hardened members who were willing to take up arms (many formerly incarcerated), he sought Elijah Muhammed’s permission to retaliate, showing respect for his leader. However, he was stunned by his leader’s answer to do nothing. He had already publicly committed to action, so the leader’s non-approval was a blow to his national stature and credibility.

Perplexed though compliant, Malcom sought to engage the efforts and resources of civil rights organizations, other religious groups and local Black politicians to address the violation of the mosque, but again in a symbolic display of power, Elijah Mohammed forbade it.

Malcom’s disillusionment set in again because he did not understand or agree with his leader’s decision. The ongoing accusations that Elijah Mohammed had conducted several extramarital affairs with young Nation secretaries was perhaps a bigger conflict, since such behavior was considered a serious violation of NOI teachings.

Elijah Mohammed confirmed the extramarital affair allegations in 1963, excusing his dishonesty by attempting to alter NOI teachings, referring to precedents set by Biblical prophets. Yet street-wise, compleat Malcom knew a player and the game when he saw them. He made a spiritual and intellectual separation from the Nation of Islam then, because he could no longer believe Mohammed or reconcile the leader’s hypocracy (on a side-note, Louis X, or Louis Farrakhan, saw in the conflict an opportunity to exploit the division between Malcom and the Nation’s leader to realize his own political ambition).

As his relationship with Elijah Mohammed frayed, Malcom became more outspoken in his own opinions and attitudes. For example, after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination of December 3, 1963, Malcom remarked,

President Kennedy never forsaw that the chickens would come home to roost so soon… Being an old farm boy myself, chickens coming home to roost never did make me sad; they made me glad. He later explained: It was, as I saw it, a case of ‘the chickens coming home to roost.’ I said that the hate in white men had not been stopped with the killing of defenseless Black people, but that hate, allowed to spread unchecked, had finally struck down the country’s Chief Magistrate.

Elijah Mohammed and Louis Farrakhan, however, seizing on that unauthorized comment, found encouragement in the national media backlash to attack and disparage Malcom directly, and Mohammed prohibited him from speaking publicly for 90 days. By that time Malcom’s popularity/notoriety had grown to the point that other NOI leaders and members considered him a threat to Mohammed’s dominance and leadership in the movement. His presence and ideas could no longer be tolerated.

Four months later, Malcom publicly announced his split from the Nation of Islam and Mohammed’s “rigid” teachings while retaining his Muslim identity. As such, Malcom confirmed that he would continue to fight on behalf of Black people and was planning to create a black nationalist organization “to heighten Black political consciousness.” He also said he would begin working with other civil rights leaders—something he had been forbidden to do under Mohammed’s dominance.

Thus began a growing antagonism between Malcom and the Nation of Islam, now competitors for adherents and influence. Many NOI members revered Malcom and were eager to follow where he would lead. It was a direct threat to Nation of Islam leadership, power and money. As a result, the negative propaganda campaign against Malcom grew, led largely by his replacement, Minister Louis Farrakhan. In early 1964, NOI leadership sued Malcom in court to evict him from his temple-owned home. Eventually frustrated, he explained his true reason for leaving the movement.

To dedicated, loyal Nation of Islam followers, Malcom’s revelation about Elijah Mohammed fathering eight children by teenaged Nation secretaries was heresy. Now speaking for Mohammed, Louis Farrakhan publicly condemned Malcom, deeming him “worthy of death,” while Mohammed Ali solemnly accessed that Malcom would die for opposing “the vessel of Almighty God.” As threats to his person and his family grew, Malcom armed himself for an inevitable final confrontation.

Self-Actualization

Tireless in his desire and effort to bring change, pride and empowerment to Black people, Malcom would not rest. He immediately announced the beginning of his own movement, called Muslim Mosque Inc., which was a religious organization, and the Organization of Afro-American Unity, a secular group that would work with other Black leaders across the globe to advance common goals.

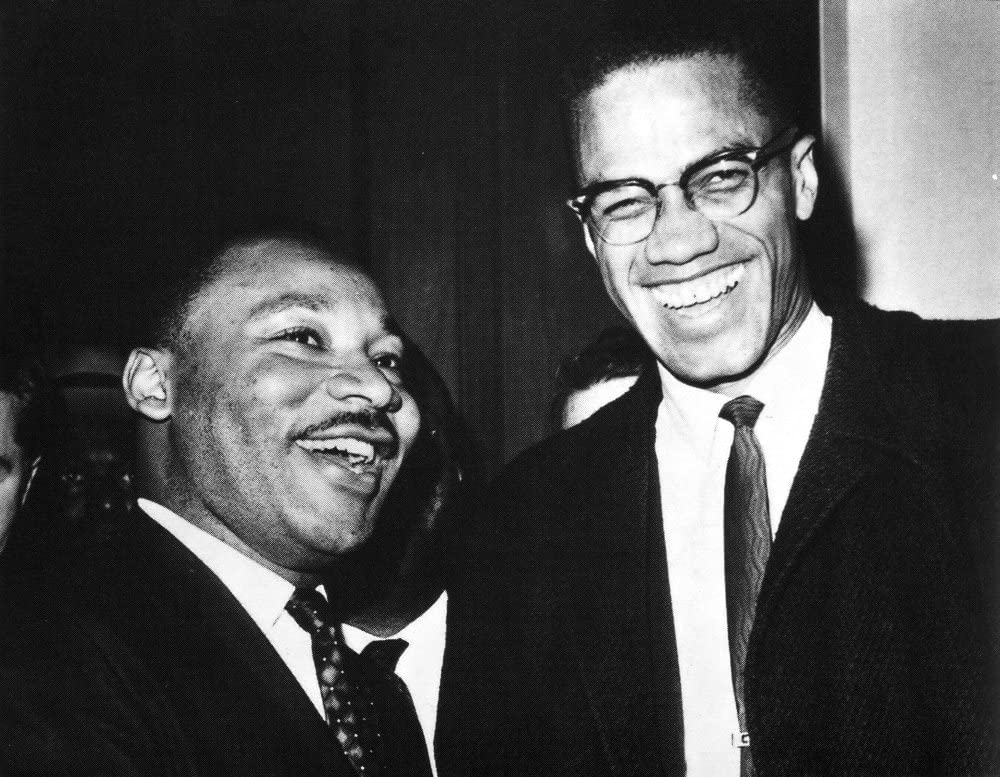

On March 26, 1964, amid NOI rancor and threats to his life, Malcom managed to attend the U.S. Senate’s debate on the pending Civil Rights bill in the Capitol building. By providence perhaps, civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was also in attendance. The two had frequently traded stinging barbs across public and media platforms, but they had never met in person. In that random and sublime moment, the two came together, putting aside their differences to pose, smiling together, for a handshake photo.

Signaling his erstwhile willingness to engage civil rights leaders and engage in the national political debate about voting rights, Malcom gave a speech called The Ballot or the Bullet, in which he encouraged Blacks to vote in their own interests rather than being taken for granted by the false white liberals who sought their votes with false promises and lies, but who always put their issues and agendas last. The speech has aged well and maintains relevance today.