Gypsy Prophecy or an Old Man’s Kind Encouragement?

As a child in Madrid, the first words I ever heard about gypsies, or the Romani people, were a warning: If you go outside the gates or you’re out past dark, the gypsies will get you, and they’ll make you work in the circus! As far as I could tell, it’s what parents told their kids to scare them into compliance.

For me, the thought of working in the circus was a fascinating prospect. The circus had lions, after all! I remember one night, hiding inside the iron bars of the fence, straining to see down the foggy street, when I saw a hunched-over old woman who was probably just a beggar, but I imagined her a gypsy, though she wasn’t scary at all. I called out an hopeful hola! as she passed, but that didn’t get me into the circus.

I still remember using stinky kerosene as fuel and the wonderful bread we ate In Madrid. I remember my father bringing home freshly-fried potato chips in a brown paper bag, still dripping with grease. They were so good!

I remember downtown Madrid, the fish market, shopping every day and the time all us kids came down with bacterial hepatitis from drinking contaminated water. We had crusty, yellow eyes for a couple weeks!

Old Madrid

At the time, we were living in a huge estate (one that actually had a name), somewhere outside old Madrid. The home was huge, but it was creepy in some ways. Surrounded by a tall wrought-iron fence, it sat more than one hundred feet off the street.

Inside the gates, to the right of the estate, there was a separate building, a garden house, with windows all around. There was a mural at the front of the home, one of Semaramis, Queen of Babylon, and Nimrud, her husband, depicted as Madonna and son.

If greeting Nimrud and his queen-mother at the front door whenever we got home wasn’t eerie enough, there was a strange mystical presence in the estate. Spiritual and intuitive, my mother sensed it early on, but my father never believed in such things.

As children at play, we would often hear seductive voices in the distance, singing our names. Thinking our mother had summoned us, we’d report to her, only to find her occupied in some remote portion of the house, where she could not have possibly called us and been heard.

In time, we all realized the voices were unnatural, so our mother warned us to be wary and not to respond. At other times, we would see the likenesses of each other in the distance, attempting to lead us away from the house.

My father never believed any of it until one night he was headed down the stairs, when something caught him by his arms and grappled with him, attempting to push him over the railing. Suffice it to say, we moved to another Madrid home before the week was through. We found out later that a woman had been murdered/hanged in the estate.

There was a gully across from our new home, where shepherds allowed their sheep to pasture. They would be out early in the morning, clothed in garments similar to those shepherds had worn for thousands of years. At sundown, we heard the bleating sheep and goats being guided away. During that time, I learned to love goat’s milk and cheese. Every once in a while, an old man on a donkey, laden with various goods and artifacts, would come down our street to sell them.

Gypsy Man

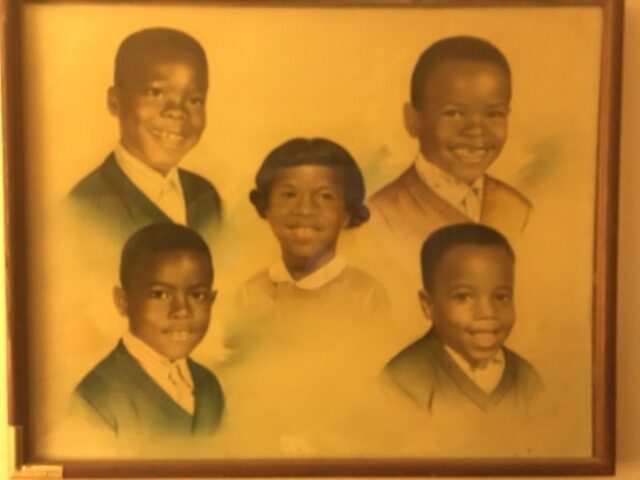

As it turned out, he was a gypsy. Over time, he became friendly with my parents, and he told them after a few months that he wasn’t really a vendor at all. He was actually a barber, who just happened to sell things. So he began cutting our hair— us four boys, until he told my parents that he wasn’t really a barber at all. He was actually an artist, a painter, who just happened to cut hair. So they asked him to paint a portrait of the children.

During that time, he took an interest in me, and he told me that there was something extraordinary in my future. He told me that he was a gypsy, blessed with the gift of prophesy, assuring me that I was destined for greatness. He predicted that I would be a prince upon the Earth, adding that, as a child, it was beyond my understanding.

For the portrait, he sourced school photos for us boys, in which we were all wearing blue sweaters, and yet in the painting, he fashioned me alone in a gold sweater, as a reminder of his prediction and benediction. Being young and more interested in crawling things than an illustrious life, I forgot his words, though the import of his message had already redirected the course of my future.

At my young age, I did not give his prediction serious thought, and yet I did not doubt the sense of conviction in his words. Since that time, consciously and sub-consciously, his blessing has shaped every action I have taken and every decision I have ever made.

Ironically, upon reflection I do not know ( and will never know) whether or not he actually was blessed with the gift of prophecy or if he was trying to infuse a young, precocious boy with a sense of hope. At this point, it does not matter, because the effect has been the same. I believed him, “and that has made all the difference.”

Living in Madrid, we watched bullfights on television in the same way that people watch American football in the United States. We understood the pomp and ceremony, and we knew the most skilled matadors. We never saw it as a sport of cruelty, as most Spanish spectators take no pleasure in watching the suffering of bulls.

Instead, bullfighting is a compassionate art, a reflection of a man’s life and an allegory to the course of the believer. In a spiritual sense, the matador is the modern embodiment of the High Priest, offering sacrifice on behalf of the sins of man.

Two Matadors (Dos Matadores—Spanish version available) a novella that I wrote in 2012, is an appeal to readers to pursue the passion in life, to remind them that it is a better thing to risk danger and death in the ring than to grow old, effete and useless, observing life experience from the stands, never having lived, while watching someone else do the things and feel the passion that makes life worth living. The story is about venturing life with passion rather than dying unfulfilled.

Antes de morir, vive!