By Marcus McGee June 18, 2021

In the News…

Juneteenth

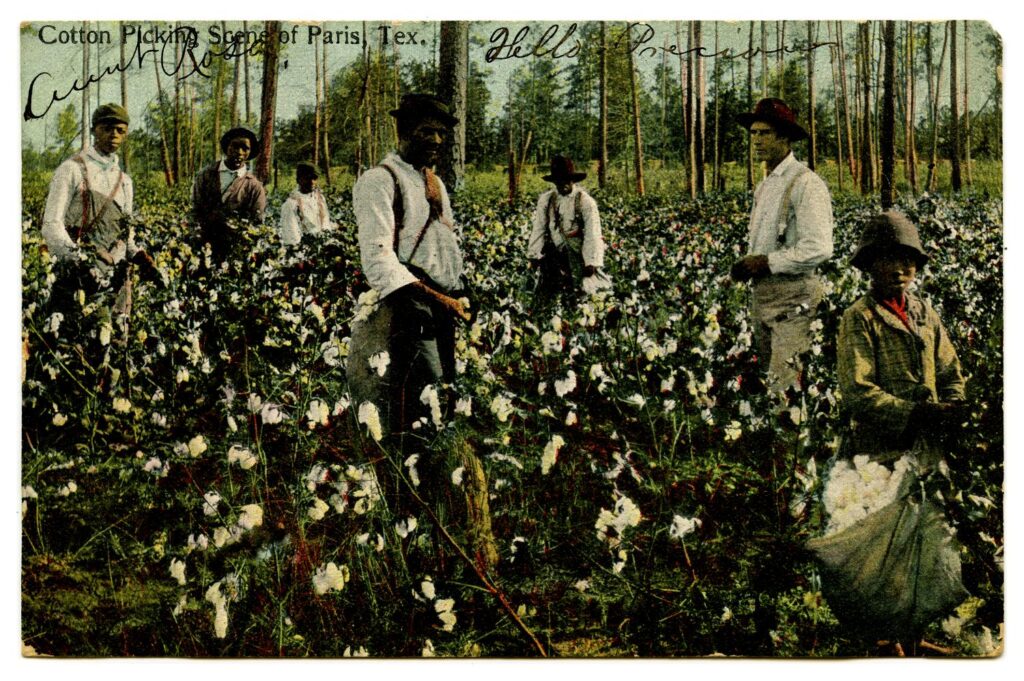

On tomorrow, Saturday, June 19, “Juneteenth” will be celebrated as a federal holiday for the first time in the history of the United States. While Juneteenth has been celebrated for years, notably on the first time on June 19, 1865 when African American slaves living in Texas learned for the first time that they were “free.” What’s remarkable is that slavery in America was abolished by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Nine hundred days! That’s how long it took for blacks in Texas to realize their freedom, extended 2.46 years late.

It was the 1800s, after all, an era before tweets, Internet stories, 24-hour news cycles, and unaided by the Pony Express, which existed as a horse-mounted mail service between Missouri and California from 1860-1861. News travelled slowly, and since Texas was the slavery state farthest west, Negros living in Texas were the last folks to get the news, which came on June 19, 900 days late, and delivered by Army soldiers at Galveston by Union General Gordon Granger.

So from the beginning, Juneteenth was a Texas thing, where former slaves celebrated the end of slavery, 900 days late. Over time, however, and because the end of slavery wasn’t being celebrated anywhere else, blacks in other states began to join the annual celebration and to create traditions related to the event, which included church and community events, barbeques, food festivals and speeches by former slaves and their descendants, the equivalent of an African American Fourth of July. It was also celebrated in Coahuila, Mexico, and in eastern Canada.

Texas House Bill 1016 in 1980 declared June 19 Emancipation Day in Texas, a legal state holiday, and on June 17, 2021, “after unanimous passage in the United States Senate and subsequent passage in the House, President Biden signed a bill making Juneteenth a national holiday.”

On an interesting note, the Emancipation Proclamation declared an end to slavery in Confederate states. However, there were two Union slave states, Kentucky and Delaware, who were not affected, and so slavery did not end in those states until after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which constitutionally abolished chattel slavery on December 6, 1865.

That was 156 years ago— ancient history in the minds of many, but we must consider the day an occasion to reimagine the psychological and fiscal impact of slavery on the the generations of African Americans who live and have lived in its wake. To reimagine slavery—an existence that was less than human, human chattel—to be owned, like a tractor, a plow or a mule—for generations. That has had an impact, a legacy that won’t be cured unless there is some intelligent, fair, counteracting weight applied on the distal dish of the skewed scales of justice.

But where’s the grist for the great stories? Think 900 days! If slavery wasn’t bad enough, imagine 900 days of living as a slave, when you were actually free. Imagine working two extra years for free when you should have never been working for free in the first place. Imagine the families hearing the news. Imagine how the relationships between slaves and their former owners changed. And the attitudes of owners who benefited from 246 years of free labor. How would the necessary work get done, and what would be the pay structure. Who were the first black sharecroppers? Imagine that first generation of freed blacks and their stories.

Certainly the wealthy black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma—just north of Texas, was a realization of some of those stories. Oklahoma was a territory that had been established for the resettlement of Native Americans from the American Southeast—many of whom had been slaveowners. Yet Oklahoma did not become a state until 1907.

Tulsa was segregated, as a 1916 city ordinance mandated segregation by forbidding either Black or White people from residing “on any block where three-fourths or more of the residents were members of the other race.” In the Greenwood District, black businesses and families prospered, largely due to serving the black community. By 1921, Greenwood was the successful community known as the “Black Wall Street,” only to be destroyed and devastated on Memorial Day that same year.

Yes, the stories are there, and it is up to us to seek them out, listen to them, and to use our unique gifts in sharing them. It’s a good thing that Juneteenth is now a national, federal holiday, but we can give it true meaning by fleshing out its bones with its unique stories, lessons and histories.